TL;DR Scroll to the bottom for the Medieval Monarchs booklet. You’re welcome.

In this blog I explain the journey that we have taken at Reach Academy around curriculum design. It is a VERY long blog (over 4000 words, which will take the average reader about half an hour) in which I explore common practices in primary around the foundation subjects, and why I think they’re problematic. I discuss the difficulty with doing the ‘right thing’ (for both teacher and pupil) and lay out the problem of being a generalist expected to design and deliver specialist content. Then I detail our solution, and the some of the evidence from research that underpins it. I think that it is probably useful for teachers of all phases.

Some of you may have seen the excerpts from a booklet that I posted on twitter, so if you’re short on time and would just like that, then scroll to the bottom where you can download it. It is still the first draft, so there are likely spag errors which will be proofed out. If you have any more substantive feedback I’d be grateful. We’ll be sharing more materials in due course, so do subscribe to this blog if you’d like to be notified when it comes available.

For the more knowledge-hungry, epistemically curious amongst you who would like to dig a little deeper into what led to it, enjoy. (I was going to break this into several blogs but I think it’s better to have it all in one place. However, you may want to read one section then return later for the other bits.)

How I used to teach

Five years ago, when I was a fresh faced trainee launched into the deep end of teaching, I was told by my deputy headteacher that I’d be teaching the stone age next term. Being new to the game, and not really knowing anything in particular about this period of history, I sought advice from more experienced colleagues. “The Stone Age?” they said, “Lucky you! There’s loads you can do with the Stone Age. The children are going to love it.”

I then dutifully wrote down all of their suggestions, which included:

- Going out onto the field and look for food to show the children how it would have felt to be a caveman.

- Building a neolithic roundhouse out of card and straw.

- Learning the Stone Age Song* and performing it as a class.

- Designing some cave painting art using mud and oil.

- Creating some stone age jewelry using beads and string.

- Burying some broken pottery and have the children ‘excavate it’.

I filled six weeks worth of lessons with these activities, and my colleagues were right, the children absolutely loved it. By the end of the term, most of the children had created a neolithic roundhouse that looked something like this:

Success! The children had all made a neolithic roundhouse! Except, none of the children really knew what ‘neolithic’ meant. Most of our time had been spent thinking about the best way to get straw to stick to card. (Pritt stick is terrible for this, in case you’re wondering.) Their lack of knowledge about the topic that we had ostensibly been studying was brought coldly to my attention when a veteran TA, Sue, covered my class for the end of the day. Often, when dropping into any class, Sue would often look at the topic display and quiz the children about it. She didn’t know exactly what they had been learning about, but Sue had amazing general knowledge, and could think of questions about any topic that you’d expect anyone familiar with it to be able to answer.

“They didn’t know that the Stone Age was split into the palaeolithic, mesolithic and neolithic eras,” she gently informed me. “So obviously they didn’t really know when these periods began and ended. And they didn’t know about how we stopped being hunter gatherers and started farming.” That wasn’t all they didn’t know. They didn’t know how old homo sapiens, our species, was, or when it interacted with neanderthals, and why they went extinct but we didn’t. They didn’t know that Britain was connected to Europe by a landbridge until about 10,000 years ago. I could fill this blog with things that they didn’t know.

N.B. This isn’t actually completely true. There were some children who knew all of that stuff. They were the children who went home and had rich conversations with adults and siblings at home. Who were taken to museums and given beautiful non-fiction books. These were invariably the children who were already attaining the highest in the class, and almost always came from wealthier backgrounds. In neglecting the rich knowledge of a topic in the classroom, I realised I was actually widening the attainment gap between the richest and poorest in society.

But I wouldn’t be so sure about what they did know. Gun to my head, I’d have struggled to give you even five facts that I was really confident that all of the children would be able to answer correctly. And the truth was, I wasn’t really clear myself on the distinguishing characteristics of the different eras. I couldn’t tell you the five most important facts; the ‘even if you forget everything else, you need to know this’ sort of stuff. So we hadn’t really studied the Stone Age. We’d ‘done’ it. As headteacher Clare Sealy puts it, we ‘do’ things in primary. We ‘do’ the Romans. We ‘do’ the Tudors. But there isn’t a whole lot of clarity around what ‘doing’ a topic means. Everything and nothing is up for grabs.

This lack of clarity has struck me particularly starkly more recently, as I’ve begun to teach an A Level at our school. After studying the exam specification, I was a little intimidated by the sheer volume of content. But one of the major difference between primary and secondary is that in secondary, all of it – every last bit – has to be taught. I can’t get to the end of the year and say, “We were supposed to have learnt the ontological argument but, you know, we had so much fun learning about intelligent design that we just didn’t get a chance – sorry guys!” Whereas at primary, you can absolutely get to the end of the World War I and think “Gosh I was supposed to spend some time talking about the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk but it’s half term now. Never mind.”.

It is common in primary to complain that there is too much accountability, too many central diktats, too much teaching by numbers. There may well be some truth to this in the core subjects of reading, writing and maths. But I think that the opposite is true of the foundation subjects. There is more or less no accountability, nor any useful indication of what is expected of children in different topics and in different year groups. Ofsted have recently indicated that they will be taking the whole curriculum more seriously, but at primary they are not, in my experience, placed under any real kind of scrutiny. Headteachers and senior leaders, too, seem unconcerned with what happens after lunch. There is almost a tacit deal: teach English and maths exactly as I say, and the afternoons are yours.

Knowledge organisers – searching for the Goldilocks spot.

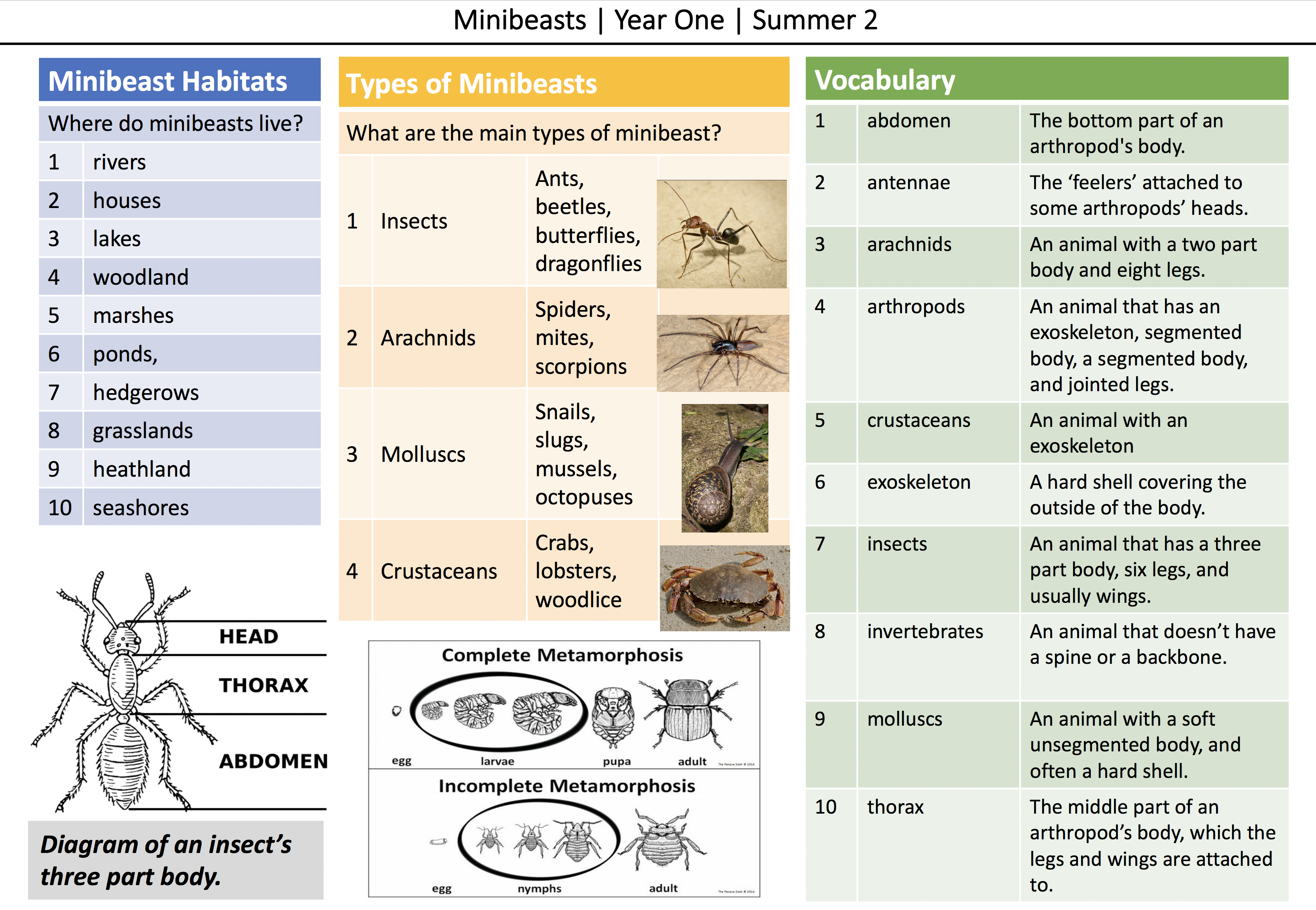

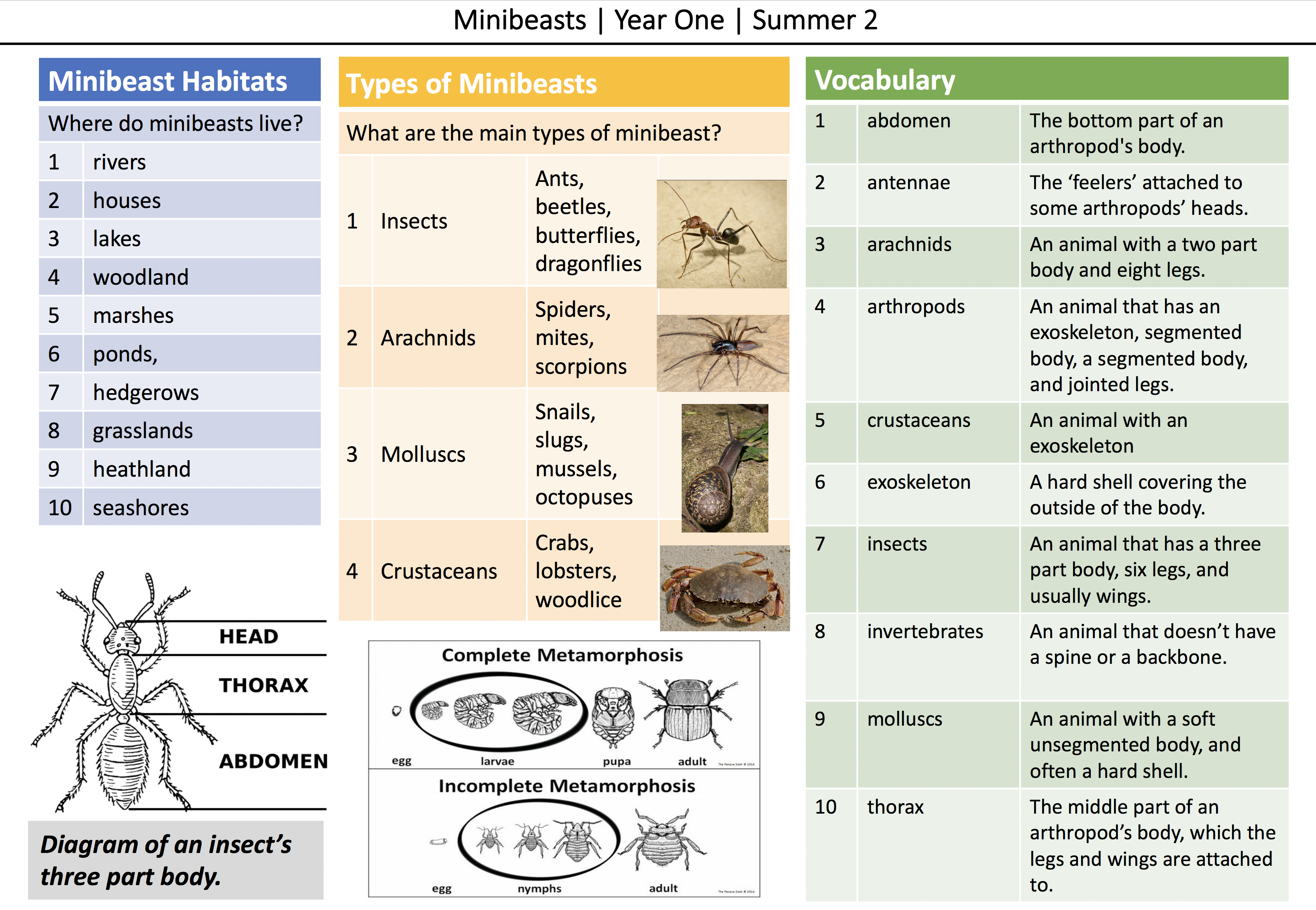

My first attempt to mitigate this and clarify exactly what was expected to be learnt was to create knowledge organisers for use in primary subjects. I first wrote about these two years ago, and won’t repeat here why I think they are so powerful and represent such a step change. If you’re interested in reading more about knowledge organisers specifically, I’d recommend this, this, this, this, this and, especially this, by Joe Kirby who I believe invented the glorious things. Here is an example of a few that we use:

Here is a Blank Knowledge Organiser Template in case you want to make your own.

I’ve been delighted to see knowledge organisers become so popular over the last few years and to see teachers think carefully about what they want children to know at the end of a topic, as opposed to what activities they want to fill lessons with. There have, of course, been detractors, and I deal with some of the most common criticisms here. Interestingly, the most common criticism on social media now seems to be that ‘everyone does knowledge anyway’. In short, the argument has shifted from ‘this is such a terrible idea that nobody should do it’ to ‘this is such a good idea that everyone is already doing it’.

We have, however, been self critical as we have implemented knowledge organisers. I am lucky enough to receive lots of feedback from teachers and senior leaders pursuing some of the ideas set out in this blog and elsewhere, and so have a grasp on the difficulties with moving to a more knowledge based approach. The most common issue is (as is usually the case) in implementation. Teachers give out the knowledge organisers, and then wait for the magic to happen. And it doesn’t. Kids tuck them away and forget about them. Also a problem is when teachers (and I have certainly been guilty of this) go into quizzing overdrive, and use the knowledge organiser almost exclusively in lessons, thinking that perfect recall of the definitions and knowledge statements equates to learning.

We also found that there was a huge variation of the quality of pupils’ work in books. Some tasks were rich and focussed on the content of the lessons, but others seemed to be tagged on as an afterthought and seemed to lack purpose. If a knowledge based curriculum – and a knowledge organiser – is supposed to be the great academic leveller in the classroom, then it follows that all pupils’ work should be of a similar standard, securing that core understanding.

From my perspective, then, there are two common mistakes with knowledge organisers:

- Focussing on the knowledge organiser too heavily.

- Not focussing on the knowledge organiser enough.

Knowledge organisers are necessary but not sufficient. Over reliance on lists of facts can lead to what Dan Willingham calls ‘inflexible knowledge’, which he illustrates brilliantly in this article for the American Federation of Teachers:

Much of what is commonly taken to be rote knowledge is in fact not rote knowledge. Rather, what we often think of as rote is, instead, inflexible knowledge, which is a normal product of learning and a common part of the journey toward expertise.

In his book Anguished English, Richard Lederer reports that one student provided this definition of “equator”: “A managerie lion running around the Earth through Africa.” How has the student so grossly misunderstood the definition? And how fragmented and disjointed must the remainder of the student’s knowledge of planetary science be if he or she doesn’t notice that this “fact” doesn’t seem to fit into the other material learned? (Willingham, 2002)

So, what is clear is that we need to go beyond knowledge organisers. Sure we need teachers, pupils and parents to be really clear on the core, necessary facts that represent a well developed schema of a topic. But we need to make sure that the explanations of – and connections between – those facts in lessons makes the knowledge memorable, flexible and transferable. Unfortunately, this brings about its own difficulties…

The Challenge

Earlier this year Policy Exchange published a report by John Blake called Completing the Revolution: delivering on the promise of the 2014 National Curriculum. In it, he begins by praising the ambition and rigour of the new national curriculum, a perspective that I share, but identifies the key problem which has led to the failure of real educational change or raising of standards in many subjects.:

Yet the promise of NC2014 is at risk. It has been enacted by teachers with little useful practical guidance and poor training in curriculum planning, based on curriculum resources (textbooks, worksheets and the like) which do not meet the high standards found in other educational jurisdictions such as Singapore or Finland. The English system has also lacked a professional body for educators to advocate for and defend standards of training and provision in curriculum.

The national curriculum at primary demands detailed knowledge of dozens of topics across 10 or more subjects. In many cases, teachers are expected to deliver this using nothing but whatever resources they can find on the internet, the process of which is so time consuming that no time is left to really develop their own knowledge (Not to mention the disjointed effect it has on pupils’ learning). This is no criticism of primary teachers (I am one), but short of being a polymath it is impossible to be an expert, or even an informed amateur, in everything.

But here’s the rub: in the meta-review What Makes Great Teaching? Professor Rob Coe concluded that (pedagogical) content knowledge is the most important factor related to teacher effectiveness. And E.D. Hirsch has shown that the ‘knowledge gap’ is what explains the attainment gap between different student groups. The more you know, the more easily you learn. Knowledge begets knowledge, and if we don’t ensure they get it in the classroom (really make sure), we’re taking a fingers crossed approach to our children’s learning.

And of course, creating all of the resources necessary to deliver a high quality curriculum is achingly time-consuming. So what many teachers, perfectly understandbly, resort to is what Clare Sealy describes perfectly as Twinkl Studies. A last minute search for a powerpoint to flick through and an activity to busy the children with for 15 minutes before storytime and home. The recruitment and retention crisis are driven in large part by the laughably unmanageable workload, and teachers having to create all of their own resources should be the first in the dock for that travesty.

Lastly, this ad hoc approach to curriculum, with nothing other than general topics specified (some which are impossibly vague, I’ve seen examples of ‘Castles and Knights’, ‘Explorers’, ‘Superheroes’ and even ‘Love Island’) it is incredibly difficult to build on key concepts. The idea of ‘democracy’, for example, is best explicitly revisited in multiple units, year after year. So too with ‘civilisation’, ‘parliament’, ‘republic’ and ‘revolution’ and dozens of others. A really well sequenced curriculum that gives children plenty of concrete examples of these concepts requires specificity and higher-level oversight.

The solution

Our solution is in many senses not particularly revolutionary (though we have tried to incorporate the latest findings from research evidence). However, in the years that I have been writing about curriculum and speaking at national conferences about it, I have not encountered many schools taking such an approach. Indeed, materials on the internet and on school websites suggest that skills/activity/enquiry-based curricula are much more common.

We are developing a knowledge-rich curriculum for history and geography which is fully resourced. I will go in to more detail about the components of the curriculum below, but the aims of our project are:

- Ensure every child has access to a rich, rigorous and knowledge-based curriculum.

- Dramatically reduce teacher workload.

As discussed above, the expectations now placed upon teachers are extremely high. Teachers need – no, deserve – all of the shortcuts they can. Perhaps shortcuts is the wrong word. Rather, we should be endeavouring to remove all of the obstacles from teachers that prevent them from focussing on their core job, delivering incredible lessons rich with knowledge and filled with joy, and making sure that all of the children in their class has learnt the stuff. We are putting all of the subject knowledge, carefully explained and written in great detail in age appropriate language, into the work booklet. Worst case scenario, you just read along together.

There are some who say that such an approach is deprofessionalising, but I’ve noticed that the folks making that sort of objection are invariably not full-time class teachers. Though their concerns, I’m sure, come from a good place, the criticism reveals a lack of understanding around the realities of having to deliver 20+ lessons a week in 12 different subjects.

We need to move away from this idea that using prepared resources is some sort of an affront on teachers professionalism. It is perhaps one of the most damaging myths in education. An actor would never say “How very dare you give me script. Who is this Shakespeare fellow and what gives him the right to dictate everything that I say. I demand to speak only words that I have written myself.” Just as a chef would never complain “This kitchen is filled with ready-prepared ingredients. Don’t you know that I am the chef. Let it be known that I will only cook with potatoes that I have personally peeled.”

Prepared vegetables are required for the chef to do her job. To exercise her professional skill. To create something beautiful. The actor cannot focus on how to deliver an award winning soliloquy if they have to spend all of their time writing the damn thing in the first place. Similarly, teachers can not exercise their professional skill – engaging students, explaining difficult concepts, differentiating instruction – without the resources that make this possible.

Just give them their bloody fish

In his pamphlet, Principled Curriculum Design, Dylan Wiliam (2013) identifies three ‘levels’ of curriculum: the intended, implemented and the enacted (the latter of which is sometimes called the ‘achieved’ or ‘experienced’ curriculum). The intended curriculum is the overall goals and high level aims of a curriculum. It can include content that is to be covered, but will usually be more objective based. In England, the intended curriculum is the National Curriculum (for non-academies, at least). The implemented curriculum is the resources, materials, lesson plans, and bits and bobs that are necessary to deliver the intended curriculum. The stuff you do at midnight on a Sunday? That’s the implemented curriculum. The last part is where the magic happens; the enacted curriculum.

Obviously, we don’t get a say in the intended curriculum (unless you’re an academy, although most primaries aren’t and even those that are tend to at least loosely follow the NC). It is my contention, and here’s the controversial bit, that teachers shouldn’t be messing about with the implemented curriculum either. They certainly shouldn’t be designing and creating the whole thing from scratch. Teachers should be spending the vast majority of their time thinking about the enacted curriculum (and a bit about the hidden curriculum, perhaps). I’ll flesh out my argument on this in another blog which will be be based heavily on the Chinese proverb ‘Give a man a fish, and you will feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you will feed him for a lifetime’. The blog will be called ‘Just give them their bloody fish’.

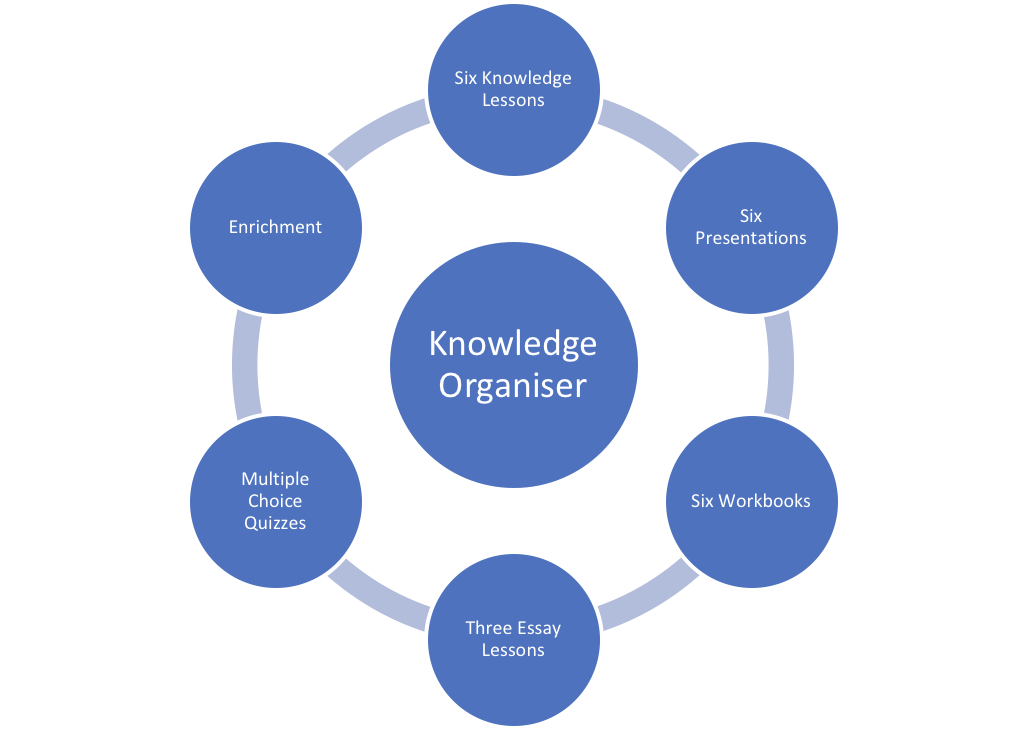

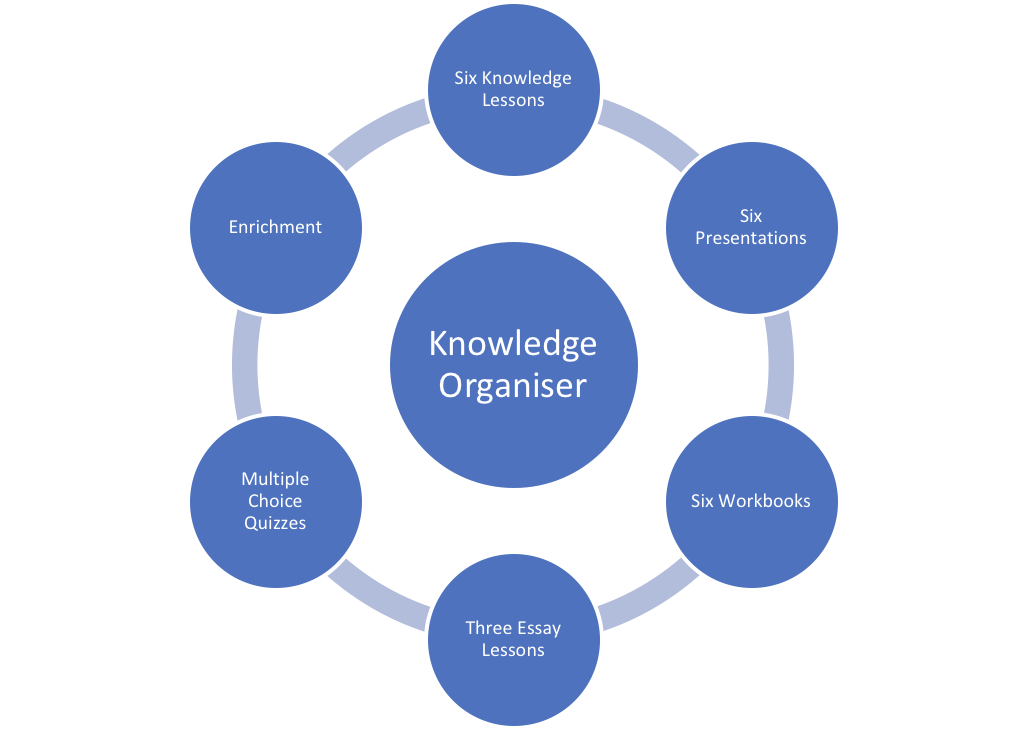

Back to curriculum, our implemented curriculum is made up of six components for each unit. They look like this and they are in a fancy graphic because I learnt how to do that on word now.

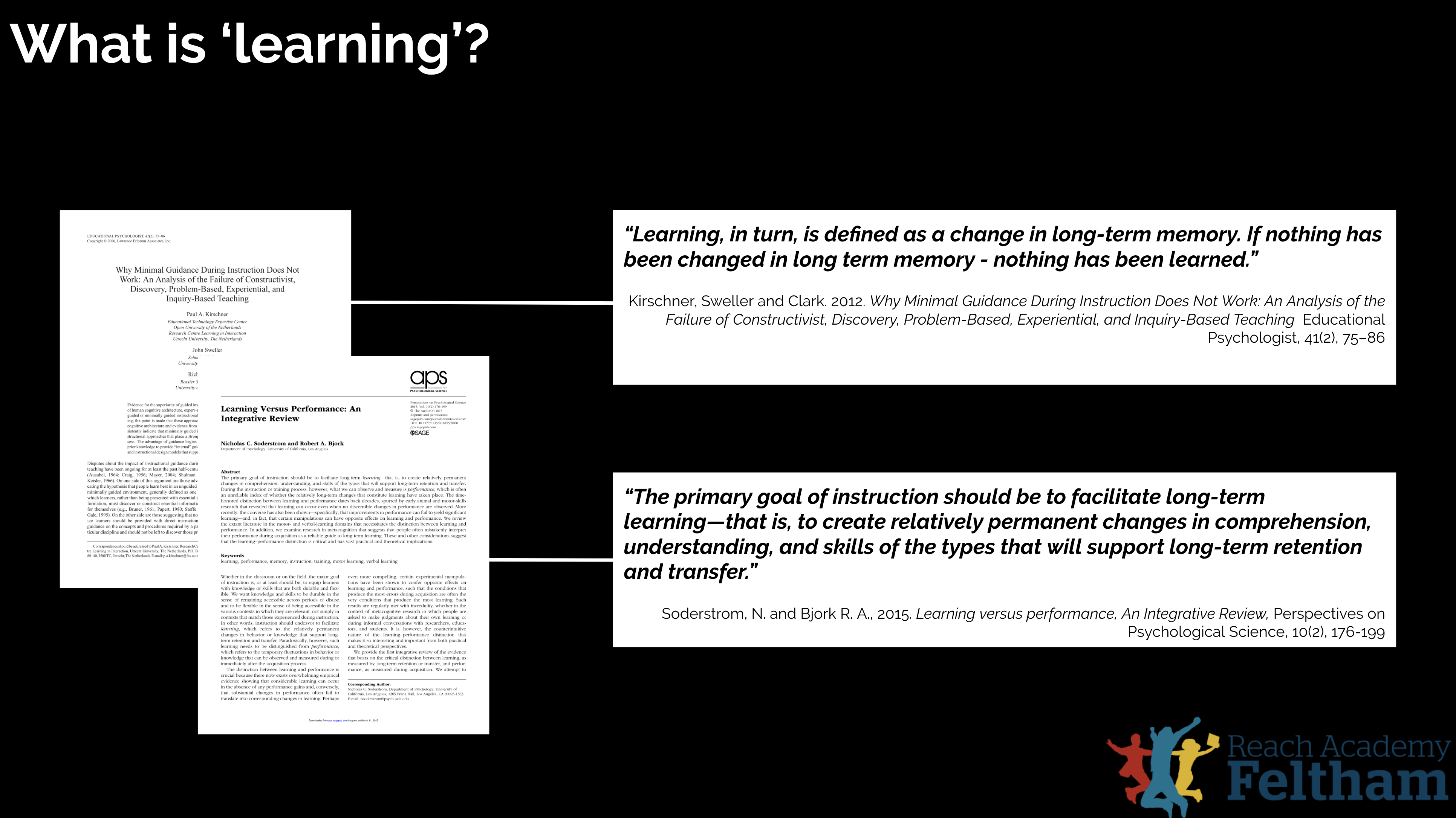

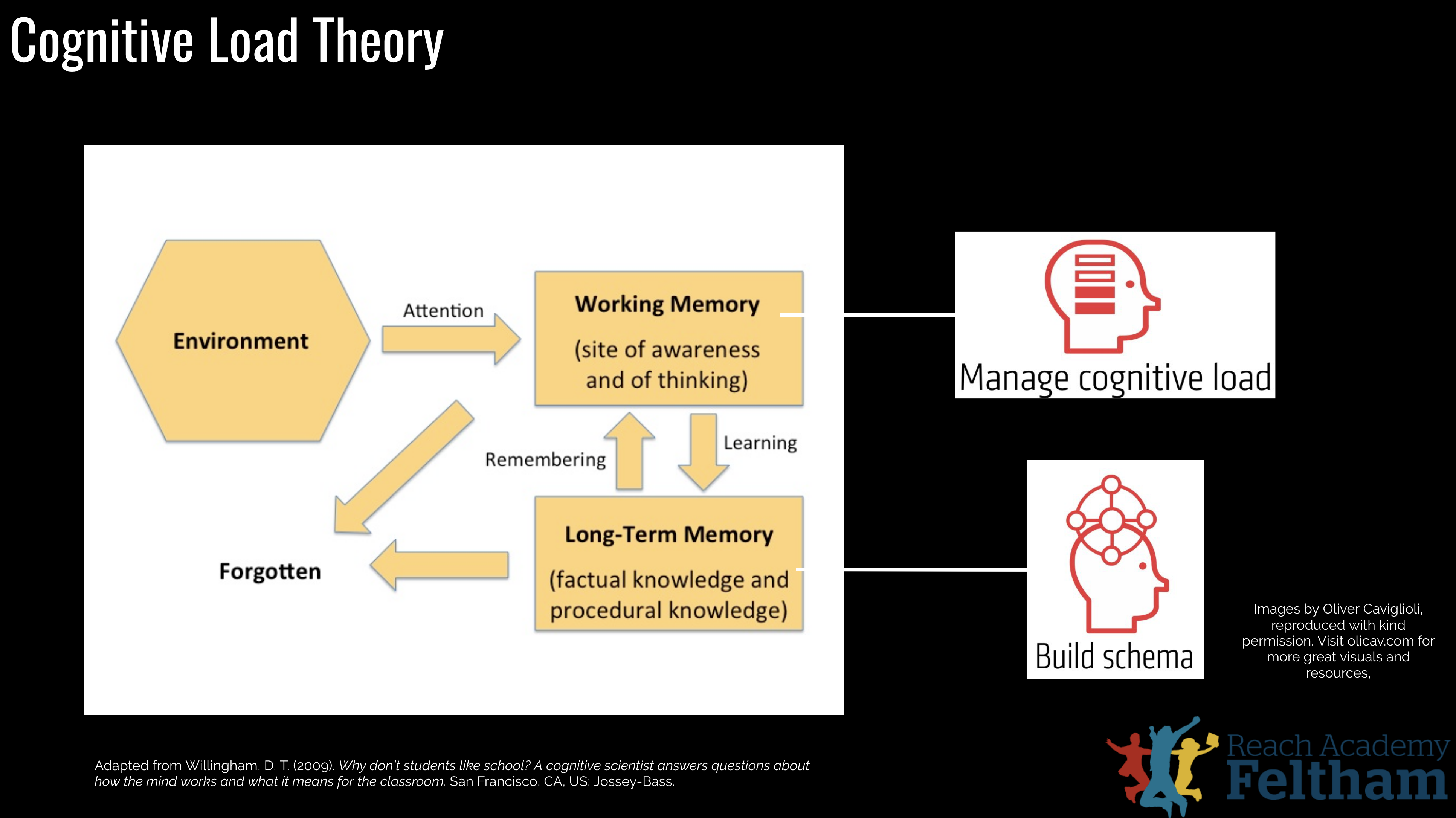

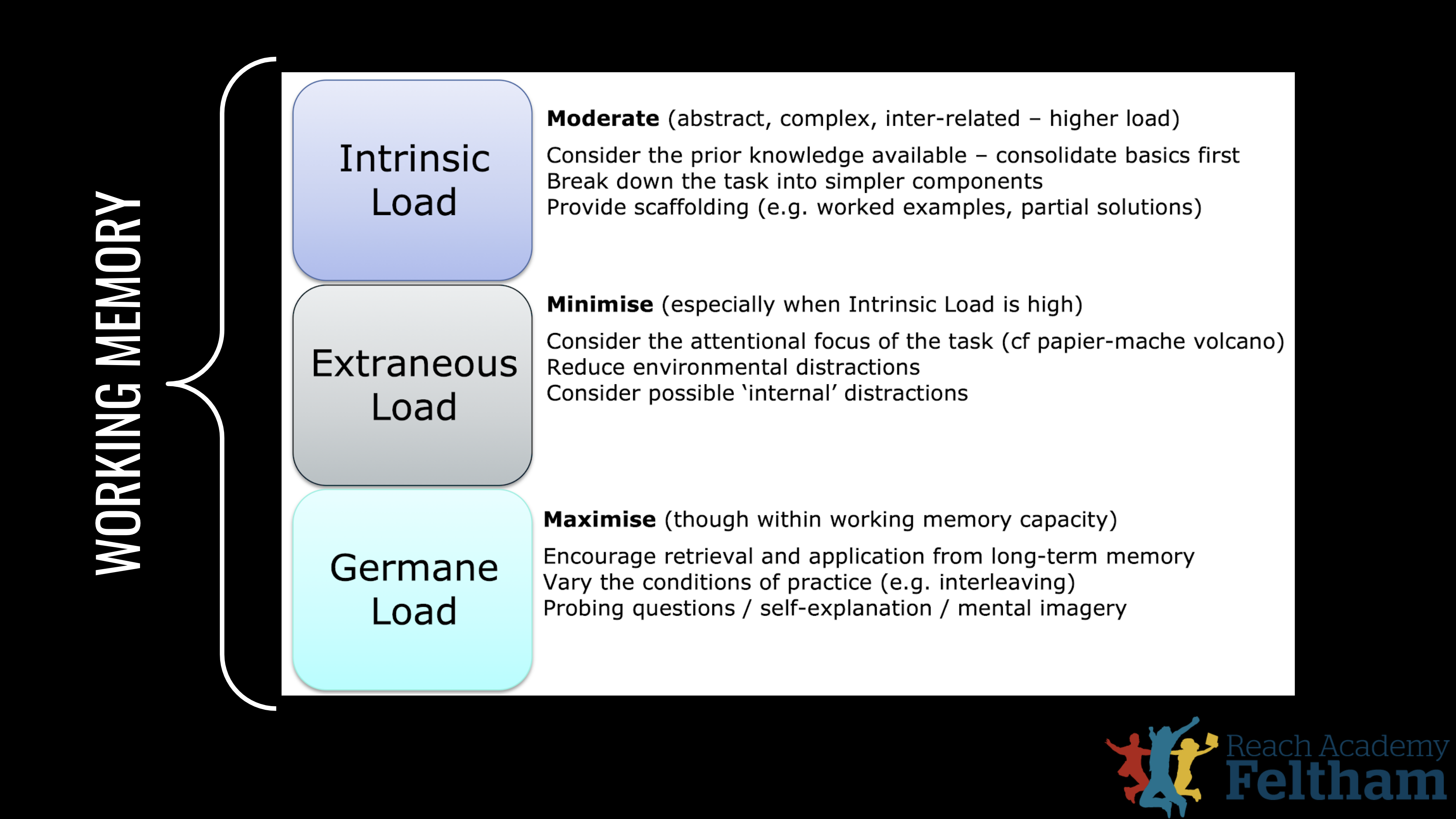

The rationale behind each of these elements was informed by the work of ED Hirsch, Daniel Willingham, Robert and Elizabeth Bjork, Michael Young, Doug Lemov, Daisy Christodoulou, David Geary, Barak Rosenshine, John Dunlosky, John Sweller, Paul Kirschner, Richard Clark, Allan Baddeley, Allan Paivio, Megan Sumeraki, Yana Weinstein, Hermann Ebbinghaus and Ian Leslie, amongst others. There isn’t space for a full explanation of the research and writing of each, I’ll save that for another blog. Each component is, however, explored in a little more detail in this table:

| Knowledge Organiser |

The knowledge organiser is the beating heart of each unit, with the core content meticulously curated and itemised to clarify the necessary (but not sufficient) knowledge necessary to develop a sophisticated schema for each unit of work. Acting as a planning, teaching and assessment tool, the knowledge organiser makes it clear to teachers, pupils and parents what is expected to be learnt by the end of the unit and within lessons. |

| Knowledge Lessons |

Each unit consists of six, carefully sequenced ‘knowledge lessons’, which can be contrasted with popular but ultimately less effective ‘activity-based’, ‘enquiry-based’, or ‘discovery-based’ lessons described by Kirschner, Sweller and Clark (2006) as “minimally guided instruction”. Our knowledge lessons ensure that the substantive content included within the knowledge organiser is brought to life, taught to the whole class utilising explicit instruction with plenty of opportunities for independent practise and application. |

| Presentations |

Our presentations support the teacher in delivering the content of the lessons clearly and precisely, whilst aiding pupil memory by making effect of ‘dual encoding’ Paivio. The benefits of receiving explanations through both the visual and auditory channel is well established in the research literature. Not to be confused with the discredited learning styles approach, dual coding can improve the absorption of new knowledge without increasing extraneous cognitive load. |

| Work Booklets |

Each unit includes a work booklet which ensures that every lesson can include rich, challenging text to be read and reviewed. Key graphics, models and diagrams can also be included to be interrogated by pupils, alongside key terms and their definitions. Questions and tasks are included for each lesson, meaning pupils get regular practise during the lesson, in line with Rosenshine’s (2012) principles of effective instruction. The work booklet very clearly sets out the standard expected in terms of class work, ensuring high academic expectations of all pupils. Furthermore, the workload of the teacher is considerably reduced as all of the necessary text and tasks are set out for them from the beginning of the unit. |

| Essay Lessons |

At the end of each unit, pupils write an extended essay. This ensures that pupils are able to synthesis and elaborate on all of the knowledge that they have acquired throughout the unit, whilst also setting them up for success in secondary school. The ability to reason, argue, persuade and consider multiple perspectives are crucial but ultimately domain specific, and so each essay allows these skills to be contextualised with the knowledge taught during the unit. Essays strengthen the storage strength of the material learnt, whilst helping knowledge to move from inflexible status to being more flexible. |

| Multiple Choice Quizzes |

The benefit of retrieval practise is one of the most robust findings in cognitive psychology. Low stakes multiple choice quizzes are efficient, effective and motivating for pupils, whilst providing teachers with vital information about what pupils have misunderstood, and/or what they are struggling to remember. These questions can be easily recycled, utilising the spacing effect and ensuring content is retained in for the long term, and not forgotten soon after the lesson or unit has ended. |

| Enrichment |

Enrichment is a key aspect of our curriculum and is sometimes referred to as the ‘hidden curriculum’. As well as motivating students through joyful and exciting experiences, evidence suggests that emotion can be extremely powerful in encoding memories more robustly. We recommend enrichment activities to take place after the knowledge lessons, as they will add to the content being learnt, as opposed to distracting from it. |

How are these resources actually used?

This post has up until now been about curriculum, but you will no doubt have noticed that the curriculum materials we have developed to lend themselves to a particular teaching style, or at least for certain teaching techniques or strategies. I don’t want to go into huge detail about the techniques here, but will certainly write about this another time. It should certainly be in the forefront of our mind, though, as Wiliam suggests that “we cannot really talk about curriculum without talking about pedagogy” (2013: p. 9) before citing Hilda Taba:

‘The selection of content does not develop the techniques and skills for thinking, change patterns of attitudes and feelings, or produce academic and social skills. These objectives only can be achieved by the way in which the learning experiences are planned and conducted in the classroom.’ (Taba, 1967: p.11)

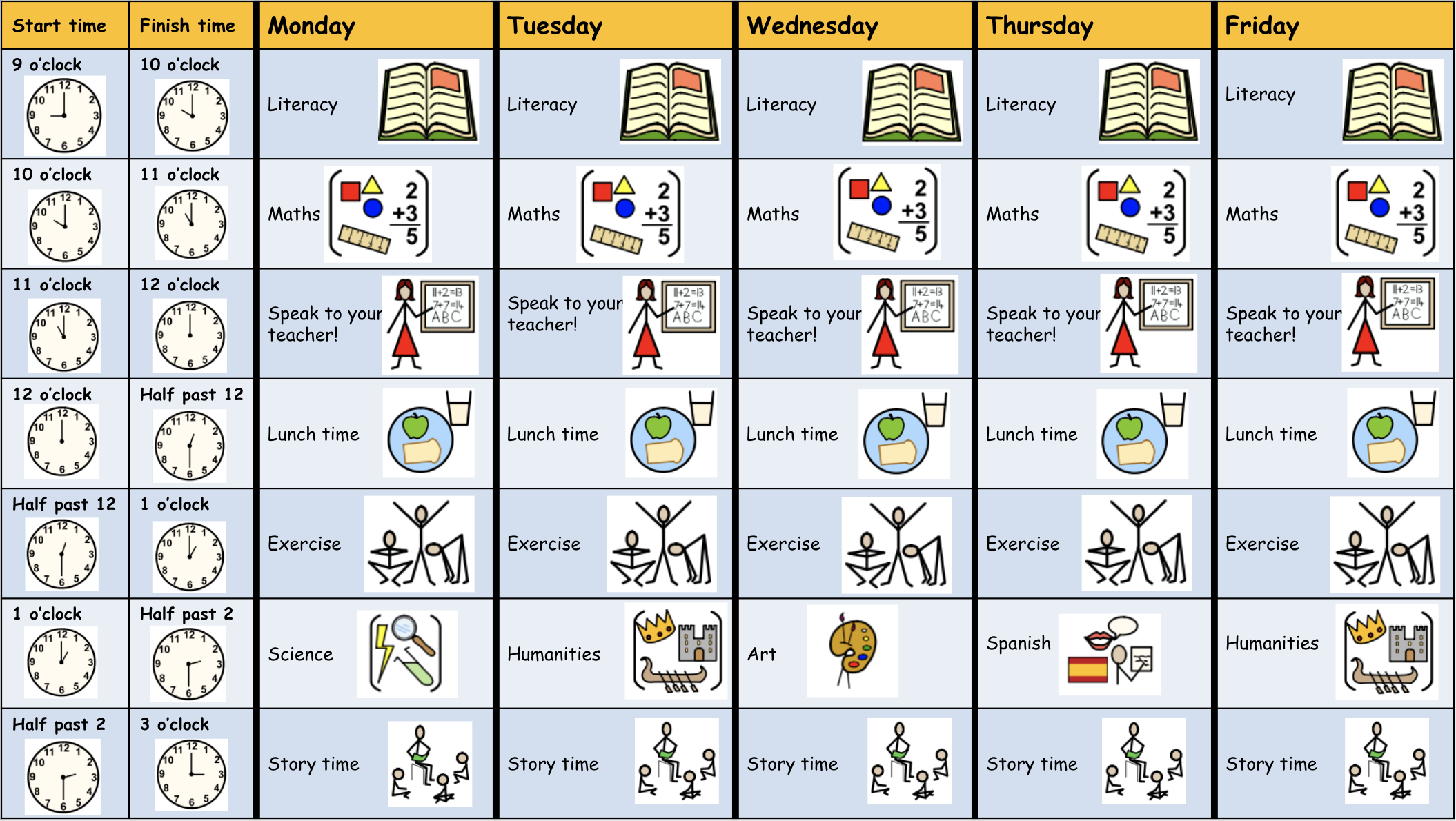

We think that this curriculum is best delivered whole class. The sorts of pedagogical techniques included in the plans are laid out here, and repeat throughout our lessons and units so both teachers and pupils get used to them and there is a coherence across the whole curriculum:

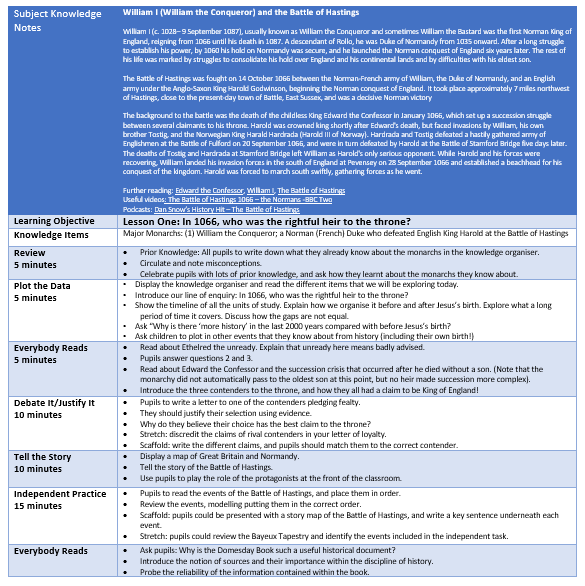

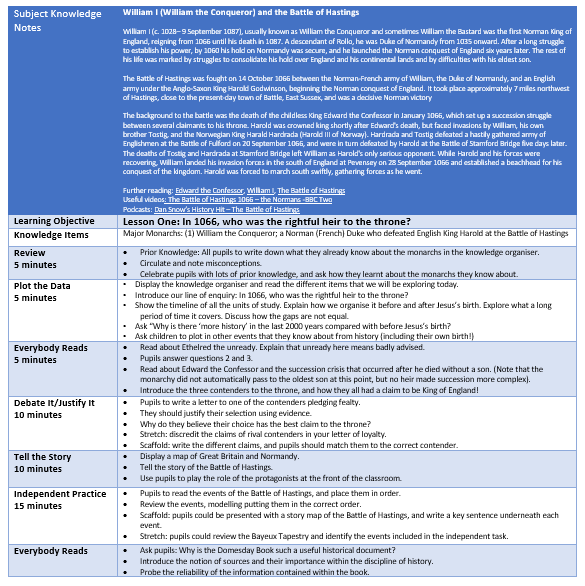

We try to keep everything in the work booklet to avoid faff for the teacher (the idea is that teachers can print them off at the start of the half term and then will never have to resources anything for the rest of the unit). However, we have also written a one page lesson plan for each lesson, which includes subject knowledge notes, and powerpoint to guide the lesson. Examples are here:

Aaaand finally, as promised, if you would like a copy of our work booklet for Medieval Monarchs to see what all of this looks like in practice, you can download by clicking this image:

Or click this link here: Medieval Monarchs Booklet

*I’d just like it on record that this is the greatest song ever recorded. Teach a knowledge based curriculum, but for goodness sake don’t forget to teach them this song.

References

Taba, H. (1962), Curriculum development: Theory and practice. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Wiliam, D. (2013), Redesigning Schooling – 3, Principled curriculum design, Available at: London: SSAT, Available at: http://www.tauntonteachingalliance.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Dylan-Wiliam-Principled-curriculum-design.pdf

Willingham, D. (2002), Inflexible Knowledge: The First Step to Expertise, Available at: https://www.aft.org/periodical/american-educator/winter-2002/ask-cognitive-scientist